Words: Nick Carroll

“It’s freedom. Freedom from other people’s ideas.”

This was Midget Farrelly’s fundamental thought about surfing. A deceptively radical thought that guided one of the truly great surfing lives.

The idea of Midget being a radical person sorta flies in the face of the narrative that sprang up around surfing’s first world champion, as the world appeared to change around him in the 1960s and ‘70s — the narrative that pinned him as conservative, unadventurous, and left behind by the times. The fact is that while Midget appeared to be all of these things, he was none of them. Indeed, Midget disliked being pigeonholed in any way at all.

He was an extremely intelligent, dryly humorous man, sardonic and intolerant of fools, who kept his own counsel, very old-school, a lifelong husband and a father of daughters, and an absolute master of wave-riding at a level scarcely any surfer’s ever managed. You can count on one finger of one hand the number of world champs who could ride a shortboard in Hawaii and steer a surf boat and its crew in Australia — and everything in between.

Bernard Farrelly had his first surfing experience in 1950, at the hands of his uncle, Ray Hookham. Big and strong, Uncle Ray was one of the North Bondi hell-raisers of the time. He took Bernard out on his 14-foot “toothpick” hollowboard, a session that scared the hell out of the six-year-old.

But the kid was also interested. By 1955 he had a 19-foot “toothpick” of his own, and a seed was planted. “Ever since I jumped on a surfboard, I knew something special was going happen to me,” he said many years later. “I just knew there would always be something special around the corner.”

In 1956, that something special was revealed to him as he rounded the corner of Victoria St in Manly, massive board in tow, and first laid eyes on the US lifeguard team — Greg Noll, Tommy Zahn and co — and their relatively short balsa “chip” boards. At the time, the world’s surf cultures existed in blissful near-ignorance of each other; the Australians had no idea you could turn a surfboard, and the Americans had no idea how badly Australians were itching to rip — how good they already were.

By 1962, Bernard was “Midget”, nicknamed thus because he was a self-described “skinny little kid” in a world of men — the likes of Gordon Woods and Scott Dillon and Bob Pike, and Dave Jackman, who’d turned their world on its head with his heroics at the Queenscliff Bombora. Inspired by Jackman’s charging, a bunch of them decided to hit Hawaii in the Northern Hemi winter of 1962/63. On the plane, Midget was heartened to see a surfing picture of his Uncle Ray on the cabin wall.

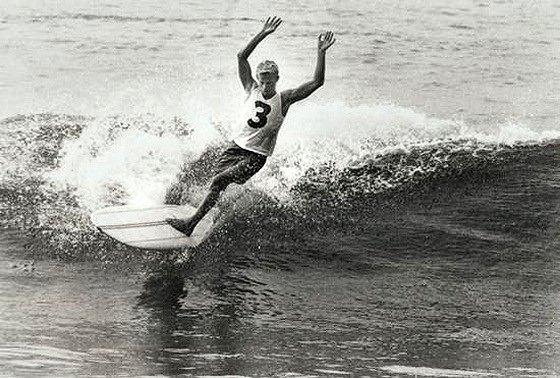

He was invited almost off-handedly to compete in the already legendary Makaha Invitational, home to the likes of Buffalo Keaulana, George Downing and company. While the other finalists sat out the back waiting for half cocked bombs that never quite came, Midget rode the inside section and enjoyed himself. He was stunned while showering off afterward to hear his name called as the winner. The trophy — a monkeypod-wood carving of a Hawaiian warrior standing in front of a surfboard — became a prized possession, beyond even his 1964 world champ cup.

The world championship in 1964 sealed Midget’s own legendhood. Yet ironically, on the back of surfing’s baby-booming popularity, it set in train almost everything he came to despise in surf culture: the surf stardom, the media manoeuvrings, the self-promotion, the drug scene, the apparent revolution in surfing styles and techniques that set Australian surfing on fire in the late ‘60s and into the ‘70s.

It also set in train the much-discussed feud between Midget and his heir apparent Nat Young, the surfer who’d become most identified with these changes. And it was a pungent feud; even in 1989, when Midget first consented to be interviewed at length by this writer, the bitterness on both sides was very clear.

But Midget hated being defined by it. And in truth, if you wanted to understand the characters involved and their effects on surfing, the Midget-Nat feud was always a kind of red herring. It didn’t tell you a thing about either person. What counted was what they did, and in Midget’s case, he simply refused to bite.

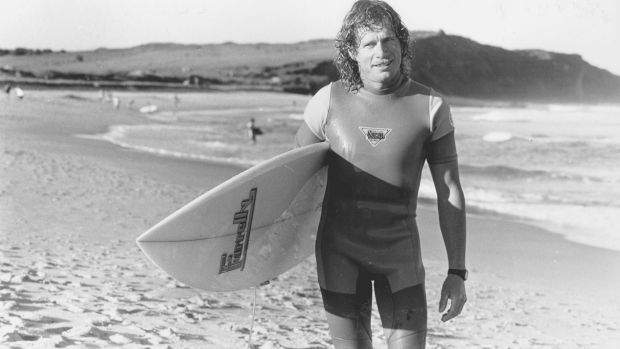

He focused on what he wanted: marriage to Beverlie and raising their daughters Priscilla, Johanna and Lucy, maintaining his foam business Surfblanks, designing and making surfboards, and expanding his knowledge of wind and water through hang-gliding, windsurfing, and eventually racing paddleboards and surf skis. He became a highly accomplished surf boat sweep, re-writing quite a few of the supposed rules of the arcane sport; casual viewers were often baffled by Midget and his all-girl crew at Palm Beach riding waves then effectively flicking off and paddling back out for more, without the chaos of a typical surf boat crash-landing on the sand.

He also continued to surf, even up to just a few weeks before his death, displaying the same serene sense of control and quiet joy that permeated his style from youth. If you’re given to the idea that surfing is a kind of art, you’ll be fascinated to know that Midget had always seen it as dance. As a child he’d done ballet classes with his sister, and the ballet teacher’s idea of structure — of moves that could be repeated in correct form — stayed with him. “Ballet teaches structure, so I structured my surfing,” he told us recently. “I disciplined my surfing so I could reach into it and pull out as much as I needed or as was necessary at the time, and I could do it on automatic.

“And I looked at everybody very analytically, all the guys who were very very good in the water. Everybody gets something from somebody else, you’re not born with it.”

There’s a truth every great Australian surfer knows in his or her bones. All, and many more besides, also know we were incredibly lucky to have someone like Midget as our bellwether, our first real champion.